Reynaldi Lindner Lolong: In 1954, Joe Papp had a brilliant idea to bring free productions of Shakespeare to the people of New York. He started on the Lower East Side, toured parks across the city, and ended up in Central Park and on Aster Place.

Drew Broussard: But that was just the beginning. What began as summertime Shakespeare in neighborhood parks has since blossomed into a year-round hub of culture, with new plays and musicals—

RLL: experimental work—

DB: live music—

RLL: international performance art—

DB: cabaret—

RLL: conversations and civic dialogue—

DB: community engagement—

RLL: and of course, Shakespeare.

DB: Through it all, the impulse has remained the same: that culture belongs to everyone, and that theatre should be of, by, and for all people. Welcome to Public Square, a podcast from The Public Theater.

DB: Hi! I’m Drew Broussard, from the artistic staff.

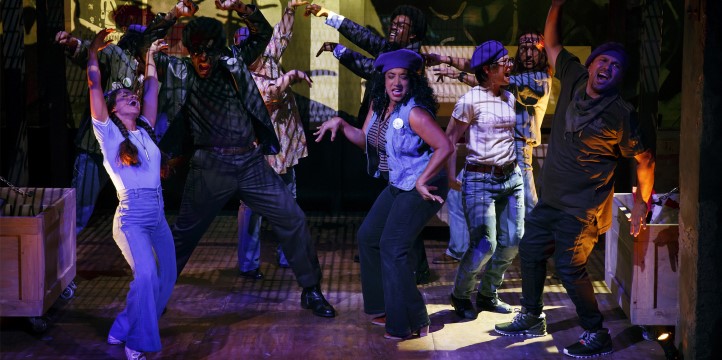

RLL: And I’m Reynaldi Lindner Lolong, from the communications team. Drew and I are sitting here in The Delacorte in Central Park, and it is a beautiful summer day. For those of you who aren’t super familiar with the Delacorte, it is our open-air, eighteen hundred-seat theater, located just off of 81st Street and Central Park West, and it is the home of Free Shakespeare in the Park. Each day, all summer long, people line up here at the Delacorte for free tickets to world-class performances.

DB: Tonight, this theater will be packed with people who will be ready to experience our current production of Coriolanus, directed by Dan Sullivan, but what they won’t see is what goes on behind the scenes: the incredible effort and the skills of our production team, who work all summer long to make Free Shakespeare in the Park possible. So for this episode, we’re gonna sit down and chat with some members of that team, and learn about what it means to work in an outdoor theater. We’ll also share a story about the land that would eventually become a part of Central Park.

RLL: But first, we’re going to go back to the first show of our season, Much Ado About Nothing, directed by Kenny Leon. We took a stroll down The Line to hear firsthand from some folks about what makes Free Shakespeare in the Park a timeless summer tradition and worth the wait.

RLL: All right, so we are here in The Line at Shakespeare in the Park, and—

[people shout “WOOO”]

RLL: [laughs] What time did you all get in line?

Interviewee 1: 5:45.

RLL: That is a commitment. And speaking of commitments, so as I’m standing with this lovely group of people, a dozen or so, you all have lawn chairs.

I1: Yeah.

RLL: You have coffee, you have chips—this is clearly not the first time you’ve done this.

I1: No. We have been to this rodeo before.

RLL: What made you want to come to this particular show, or make you want to see Shakespeare in the Park?

Interviewee 2: Well, it’s like an iconic New York thing, and I wanted to, like, show them iconic New York stuff because they’re here visiting.

Bystander [muffled]: And it’s free.

I2: Yeah, it’s free.

[laughter]

I2: Danielle Brooks from Orange is the New Black is in it; did you guys know that? Yeah, I’m really excited to see it, I think it’s going to be so cool. Well, if we get in. I dunno.

[laughter]

RLL: So I heard you saying you drove up from DC for this.

Interviewee 3: Yes, we did.

RLL: There’s a story there.

I3: Yes. So, I used to live in New York years ago, and I knew about Central Park, The Delacorte Theater, and Shakespeare in the Park, and I enjoyed it, told my husband about it, and then, um, quite accidentally a few weeks ago, I saw that the production was an all-African American cast, and an African American director. I told my husband about it, and he says, “We’ve gotta be there.” And so we planned! And here we are.

RLL: And is this your first time waiting in line for a Free Shakespeare in the Park?

Interviewee 4: No, actually this group of friends that I’m with today, we do this pretty much every summer since we were in middle school. So, now we’re all in college—

RLL: Oh my gosh.

I4: Yeah.

RLL: And so, have you seen every single production since?

I4: Not every single production, ‘cause there’s two a summer, so we try to do at least one, depends on schedules.

RLL: Okay.

I4: And then of course when there’s somebody, like, really great, you gotta make sure you see that great celebrity, like, acting. Like, the great part about Public Theatre is you get to, yeah—Amy Adams or Jesse Tyler Ferguson, when you see these people that you love from afar and then get to see them do theatre, and for free, and in this like, beautiful space, it’s like, unique, so you gotta grab that opportunity, y’know?

RLL: And do you have a favorite production that you’ve all seen? Is there a group consensus?

I4: Well, there’s not one; they’re all unique and they’re all different and like, fun.

RLL: What advice would you have for someone who thinks like, Oh, I really don’t wanna wait in line or maybe that Shakespeare is not for me, like, what would you say to like, the person who’s kind of on the fence about whether they should wait in line or not?

Interviewee 5: Yeah, don’t come because it will be shorter, but also—

[laughter]

I5: For us, part of the big appeal is waiting, because we make it into a brunch and a hangout with friends in the park for a day, so don’t make it into waiting in line; make it hanging out with friends.

RLL: Awesome! Thank you so much for your time.

RLL: For more than 50 years, Free Shakespeare in the Park has been a time-honored New York City tradition, but what many people might not realize is that behind every performance at The Delacorte Theater is an astounding crew that works day and night to make Free Shakespeare in the Park possible every summer. Today, we are joined by members of our production staff who are going to take us behind the scenes of what it really means to be a part of Free Shakespeare in the Park.

CJS: I’m Caity Joy Smith; I’m a Production Manager here at The Public Theater.

CAV: I’m Cristina Ayon-Viesca. I’m an Assistant Production Manager at The Public Theater.

BS: I’m Barry Stagg, an Associate Production Manager here at the produc—

CJS: A new title, well-earned.

BS: Thank you.

DB: We have the whole gamut, kind of. What does that mean? What does it mean to be a production manager at The Public Theater?

CJS: That’s a good question, and not a super easy one to answer. We’re in charge of managing the design and budget process for the show. Um, when we introduce ourselves to actors on the first day of rehearsal, I always say, “All of the stuff that you touch and all of the people responsible for the stuff that you touch, we worry about.”

BS: And I like to—

DB [at the same time]: That’s good.

BS: I like to say, “If you know what I’m doing then—”

CJS: You’re not doing your job—

BS: “I’m not doing my job right.”

[laughter]

BS: Like you should see me, and you should be like, John Leguizamo is like, “Hey man! I see you every day.”

CJS: “I have no idea what job is!”

BS [at the same time]: “What do you do?”

[laughter]

DB: Is that sort of part of the mystique, that you feel like you are the kind of integral glue behind the scenes?

CJS: I don’t know, I feel like that’s like, a personal philosophy on production management; I don’t think everyone feels that way; I think that’s something that like, our team likes, is to make it so that people can think about what their job is and not all the stuff that gets in the way.

CAV: All of the miscellaneous stuff we worry about, all of the—at the park especially. Things get wet, so we’re the ones that impede that, you know, that make that it doesn’t happen, and people can actually design a show, um.

DB: Right. Had any of you ever worked outside before you got to The Public?

CJS: I hadn’t, no.

CAV: I had. Yes.

BS: Yes.

CJS: I also want to be clear. Cristina said that we try to make it so that things don’t get wet, but that’s not possible. [laughs]

BS: Yeah, yeah. Oh, yeah, yeah, there’s no—

CAV: We try.

BS: There’s no—there’s no roof over the stage or the house.

CAV: Equipment, I don’t know.

CJS: Yeah, we try. We do our best.

CAV: Yes.

CJS: And then we deal with the consequences.

CAV: But we do, we do get very wet.

DB: So, so this leads into a question that I think everybody’s always curious about: what are some of the unique challenges about working at the Delacorte, versus working in a theater down here?

CAV: Um, animals, for sure.

[laughter]

CAV: Raccoons are everywhere.

DB: Yes!

BS: Um, animals are certainly a thing. Also I don’t think what people realize is by union rules, we only get X amount of hours to rehearse with our actors, and because we’re outdoors, half of that—normally, in a normal tech process, you get 52 hours onstage with the actors in costume under lights; this time we only get half that, because it doesn’t get dark until 8:45.

DB: Ohhh.

BS: So we have to redo it twice, so we’re actually taking these large shows in about half the time, and if you’ve seen Free Shakespeare in the Park, it’s not just that we do free Shakespeare in the park, it’s that we do the best Shakespeare for free in the park. So it is quite a monumental lift that our lighting—our lighting department works 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 a.m.

CJS: Yes. Every day.

CAV: And that means that costumes don’t get tech done ‘til just a small part in the day, because we can’t use them during the day, because it’s so hot outside.

CJS: Teching in the park does not look like teching anywhere else. It is just an entirely different beast in every regard. People are working under conditions they’re not used to working under.

BS: Right.

DB: What does it mean for you all to move up to the park? For those of you who don’t know, the park is not open year-round, but we are producing downtown year-round. So what does it look like to move uptown?

CJS: So, this is actually a process that Barry has sort of spearheaded for the last few years. Our departments come in in March, um, and start opening up the park, setting up offices. Every year, we have to essentially put a deck on the stage of The Delacorte Theater, because the stage is actually a dome for rain drainage, and so we have to sort of even it out so that we can—

DB: Oh!

CJS: Yeah, so that we can, um, build a set on top of it. And that’s—that’s a very time-intensive process. And it snows while they’re doing that! So then, you either have to wait for the snow to melt, or you have to shovel the stage so that you can work, and Barry’s sort of up there facilitating that process.

BS: I think before we go any further, it needs to be stated that our crews and our operations staff—

CJS [at the same time]: Incredible, incredible

BS: —are the best. Like, they are top-notch; they get put through, y’know, snow, intense cold, intense heat, rain. And we do not stop. We very rarely call a work call, ‘cause if it’s raining we’ll just kind of go underground, where it still sort of rains underneath, um.

CJS: It does.

BS: And I think what other people might not know is that we don’t own anything at The Delacorte. All of the lights, all of the speakers, all of the cable goes out at the end of the year, so we have to put it all back in: all of the infrastructure.

DB: Oh, wow.

BS: Yeah. Nothing is there. So, like the speaker web above us—above the house—has thir—

CJS: We do own the speakers now. [laughs]

BS: Well, there’s thirteen miles of cables alone in there—

CJS: Yes. Yes.

BS: —that we have to take out.

CAV: The truss is not there as well, for the lights.

BS: Mhmm.

CJS: It’s essentially an—and when you walk away from a theater for several months, and let the elements have at it, there are a number of things we have to deal with coming in every year. Every year we do a walk-through at the beginning of the year to like, I don’t want to say “assess the damage,” but assess the damage, to figure out what, since the last time we did repairs, like, what we actually need to do for the coming year.

DB: Huh.

CJS: And so that means, you know, every year we have to put grip tape on every single rung of each lighting tower, like, little things like that that you would never think of we do every year, to make sure that it’s actually an operable theater.

DB: How are you—how are you preparing your staff for this?

CJS: Cristina, you were new to the park last year.

CAV: Yes.

CJS: Do you want to talk about your experience?

CAV: I think it was just like, rolling with whatever we had in front of us, um, so I think it’s just like digging into it with the best attitude and not letting that affect you.

DB: You have to hire the right people. You can’t—you can prepare them as much as you can, but hopefully the work on our end to find the type of people that we think will be flexible, with the right attitude—

CJS: And if someone’s not excited to come work in the park, they’re not gonna enjoy it.

CAV: Yes.

CJS: They’re just not.

CAV: Exactly.

CJS: So, I think—I mean, we’re talking about all the ways it’s really difficult, but it’s also like my favorite thing to do. It’s like, magical and special and wonderful, and the spirit and environment up there is like nowhere else, and I think that if you—if you staff your crews with people who like, who really enjoy that and feel nurtured and fulfilled by that, then they—the grueling work is just like, adds to the fulfillment, honestly.

BS: Yeah, and it’s nineteen hundred seats, so it’s bigger than almost every house on Broadway.

CAV: It is.

BS: Like, the Broadway theater where King Kong was has seventeen hundred seats; this has nineteen hundred seats.

DB: Wow!

CAV: Yes.

BS [at the same time]: Yeah. But it feels so close, so it is an intimate nineteen hundred seats, so when you get there, it does have this type of palpable energy when the show’s about to begin. And normally, when you give away tickets for free, the threat is that people won’t honor that free ticket, and they’ll be like, “Oh, I got it for free; I won’t go.” But to see a packed house of nineteen hundred people—

CJS: Every night, yeah.

BS: —all the—for free, when really there’s no lost investment for them to not show up, but they must be there—

CAV: Or even when it rains, people don’t leave and they’re just like, waiting for the show to resume, and people just squeegee the deck, it’s really, really great, honestly.

CJS: Something that I really appreciate about working up there is like, because there are so many things we cannot control that we can control in a normal theatrical environment, we—there is, like, there is a different spirit of like, all hands on deck, roll with the punches, that is required when you work up there. I was thinking about interesting Delacorte experiences this morning, and I was reminded of when we did our Hair to Hamilton gala a few years ago, and there was a threat of rain, a big threat of rain for a long time. And um, we had, uh, a company of Chorus Line dancers coming in and they wanted us to lay down a Marley floor so that they could do their number, and what we know from many years in the park is that Marley floors, when wet, are very dangerous.

BS: Uhhuh.

CJS: And so—

BS: Slip-and-slide.

CJS: Oh yeah. And so—

BS: Chorus slide.

CJS: So it was—[laughs] Thank you, Barry.

[laughter]

CJS: Um, so it was the, it was the night before the gala and because the gala is a one-day event, we sort of like tech the most technically intense moments the night before, and so it was just getting dark, we were about to tech that moment, and we were going to tech the Chorus Line number. And, um, a ton of us were standing in a circle, looking at the weather forecast, talking about how it didn’t make any sense for the Chorus Line dancers to rehearse on a Marley floor if they weren’t going to get to perform on a Marley floor. And so, maybe twelve minutes before they were supposed to be onstage, we all made the call that no, actually, we needed to take this floor up—this is a seventy-foot stage—because the weather forecast was telling us it was very unlikely that we would be able to have the floor in for the show the next day. And so, in that moment, I remember—we all, every single person in the theater who knew how to use a screw gun, was on that stage, including like, our production executive Ruth Sternberg. I have a picture on my phone of like, her with a screw gun in her hand in the middle of the night.

BS: Yeah.

CJS: —like, taking that—you know, taking up the deck in The Delacorte, and it’s just that sort of spirit that everyone like, looks at each other and they’re like, “All right, we’re gonna do this!” And then we just do. And that’s—I don’t think—I mean, I think situations like that do happen in more controlled theatrical environments, but like usually because you’ve done a bad job, not because there are just so many completely uncontrollable things tha—

BS: Which is great for me; I like a certain amount of unknown.

CJS: Yes.

CAV: Oh, yes!

BS: In certain departments, in certain theatrical trainings, like, train you to not have any of these unknowns, that we really need to eliminate those, but um, not us.

CAV: I mean—

DB: I want to hear more stories. Cristina, Barry, I know that you—like, what are some of your favorite Delacorte memories?

BS: Well, last year when I was loading in the house, because we have to like, tech the show in the seats, so we have to bring expensive equipment down and there are tents—we set up these large tents—and I was like, “I can’t remember if we tie these down? I’m just—”

[laughter]

CJS: Oh, Barry.

BS: “I’m just gonna leave them for now, ‘cause—”

[gasps]

BS: “And I’m gonna ask my boss then, John, tomorrow or something.” And sure enough, there was like the biggest hurricane-type gale force—

CJS: That was Othello. That was me!

BS: That was you?

CJS: Yes! [laughs]

BS: And the 10x20 foot tents just lifted off the ground!

CAV: Oh my god.

CJS: And some of them, they were tied down, and so the legs of the tents, the aluminum legs just bent in half.

DB: Wow.

CJS: Because of the wind.

BS: Tarps. It was like full Wizard of Oz, like houses lifting off the ground—

CJS: Yes.

BS: And I just remember Tony Award-winner Jess Paz going like, “oooOOOOOHhhhhhh!”

CJS: Oh, man. And then we had to have everyone take cover, everyone had to go under the deck, because there were—it was like, dangerous winds. And it was the end of the workday; it was like 5:55 on a Monday, so everyone was going to leave at 6:00, but we couldn’t let them leave because there was—it was dangerous.

BS: Yes.

DB: Wow.

CJS: And so we all—we had everyone hunker down, the whole crew hunkered down in like, the dressing rooms, and under the—under the deck.

CAV: But now, me coming in, this new—like, this year, I have all that insight. You know, he’s like, “Make sure you tie these down.”

[laughter]

CAV: Otherwise that’s how you learn.

CJS: Cristiina, you gotta have one.

CAV: I think—

BS: Well, because Cristina, you were stage manager last year—

CAV: Yes.

BS: —and now are on staff with us as production manager.

CAV: Yes, exactly. So last year, I got to squeegee the seventy-foot floor.

CJS: Thank you. We appreciate it.

CAV: The whole deck.

CJS: You’re wonderful.

CAV: I would ge—we would get applause everytime we would come out with squeegees.

CJS [at the same time] Yes.

DB: Oh hell yeah.

CAV: I gotta go with the—

BS: Oh, Desdemona, on the bed—

CAV: Oh, yes! So I was backstage, doing my trackg, backstage right, and I just hear James, the PSM on radio, telling us to get towels ready. You know, light rain started, we’re going through the show; it’s the last scene—it’s a twenty-minute scene—but it’s the last one, so he really wants to get the show in. Um, drizzle starts, a little heavier, heavier rain, and then we’re like, “Okay. It’s five minutes. People are gonna be fine. Let’s just have towels ready; let’s be, you know, ready for the actors and then—” Mind you, twenty minutes go by with um, Heather—no, Alison, right? yes—she was laying on the floor because she’s dead, throughout the whole scene. So a puddle started, like—

DB: Oh, man.

CAV: —just, accumulating around her head. Um, we just never thought about it, and then she just like—blackout, she leaves the stage for curtain call and her wig is literally falling off her head. She’s so wet. We’re like, “Oh my god, we’re so sorry,” and she was like, “Guys, you’ve gotta think about me. I’m literally dead for twenty minutes, and nobody, like, cared.” We’re like, “Oh my god. Okay, noted.” So yeah. That was—

[laughter]

CJS: Oh man. We have to have a good racoon story, right? Can we just talk about racoons for a little while?

DB: Yes.

CJS: Is that allowed?

DB: Yes.

CJS: Um, we—racoons are very intelligent creatures and know how to get into things, and so, um, I believe Barry Stagg has a photograph on his phone of a racoon in a refrigerator, um, at The Delacorte Theater.

BS: Yes, eating salad.

CJS: Eating salad.

BS: With its hands!

CJS: With its little opposable thumbs.

CAV: That, that made my family very happy. They were like, “Is that your job? Is that what you do?” I’m like, “Yes. Exactly that. I am a racoon wrangler up at the park.”

CJS: Oh, and the racoons ate the styrofoam peaches this year in Much Ado About Nothing, ‘cause they—they would, like, take more than one bite out of the peaches.

BS: Just in case?

CJS: I guess, yeah.

BS: Honestly, I’m pretty sure I’m the same way, like, if I eat something that’s like, that doesn’t taste good, I’m like, lemme try one more time.

CJS [at the same time]: Lemme try one more time.

[laughter]

DB: Um, one last question, to send us off on—on a high note. You kind of already answered it, but like, is there advice that you’d give to somebody who’s out there listening to this who’s like, “I wanna work in the park!”

CAV: I don’t know. I honestly like, I knew I wanted to work at The Public and I just like, had that objective very clear, and I just worked outside, got the experience I needed, and then literally cold e-mailed The Public. And then I was lucky enough that Peggy Carey—yeah, shoutout!—saw my resume and called me in for a stage management gig, and then it’s just like, getting to know the institution and getting to—getting to know what you like and what your strengths are, personally, to serve the bigger goal better.

BS: You know, also, all glitter is not gold either. Like, work is work sometimes too; like, some people think getting to The Public, getting to The Delacorte, is the finish line, but it certainly can’t be. Like there’s so much work after that, and there’s so much room for growth as a person and a professional there.

CAV: And even like, every day is different, so it really is—you have to come in with your best attitude every day and just like, work and work and keep working and like, being the support that your team needs.

CJS: A lot of theaters you don’t have, like, a team of production managers, and we really have a team here, and it’s an enormous gift, because we all have very different strengths, and I think that we are able to assemble groups that really support each other and allow us to like, bring our humanity to work and be, like, the people that we are and also excel. And that’s, I think, rare. And very cool.

KM: Hi! I’m Karina Mena, a Marketing Associate here at The Public.

If you head up north from the Delacorte, veering towards Central Park West, away from the reservoir, you’ll enter an area formerly known as Seneca Village. Located on the West Side between 83rd and 89th streets, Seneca Village began in 1825, when landowners in the area, John and Elizabeth Whitehead, subdivided their land and sold it as 200 lots. Andrew Williams, a 25-year-old African American shoeshiner, bought the first three lots for $125, followed by Epiphany Davis, a store clerk, who bought twelve lots for $578. From there, a community was born, and by the early 1830s, there were approximately ten homes in the village.

Despite New York state’s abolishment of slavery in 1827, discrimination was still prevalent throughout New York City and severely limited the lives of African Americans. Seneca Village’s remote location likely provided a refuge from this climate and created an autonomous community. Census records show that residents were employed, owned property, and that most children who lived in Seneca Village attended school.

By 1855, approximately half of Seneca Village residents owned their own homes; property ownership provided rights not commonly held by African Americans in the city at this time, mainly the right to vote. There were only a hundred black New Yorkers eligible to vote in 1845; ten of them lived in Seneca Village. Unfortunately, this vibrant community was not to last. In 1853, the New York State Legislature enacted a law that set aside 775 acres of land in Manhattan to create the country’s first major landscape public park.

And, in 1856, the city began clearing the land through Eminent Domain, which allowed the government to take private land for public use. Ultimately, all residents of Seneca Village were evicted by the end of 1857, and dispersed, and it is unclear where Seneca Village residents were relocated.

For decades, scholars and archeologists have worked to resurrect the history of Seneca Village, which was seemingly erased until 2011, when an archeological excavation of the area uncovered significant remains. To learn more about Seneca Village, the efforts to preserve its history, or to sign up for a walking tour, visit centralparknyc.org.

DB: If we’ve peaked your interest in Shakespeare in the Park, or you weren’t able to make it to The Delacorte this summer, we have exciting news: this summer’s production of Much Ado About Nothing was filmed for PBS’s Great Performances series, and will be airing on November 22nd. You can check your local listings for more details. Meanwhile, thanks to Jack Phillips Moore, Barry Stagg, Cristina Ayon, and Karina Mena. Music for this episode was by Michael Friedman, audio engineering by Dani Lencioni. Thanks very much! We’ll see you next month.