Fernando Masterson: In 1954, a man named Joe Papp decided to bring free performances of Shakespeare to the people of New York. He toured the parks across the city, eventually ending up in Central Park and on Aster Place.

Reynaldi Lindner Lolong: But that was just the beginning. What began as summertime Shakespeare in neighborhood parks has since blossomed into a year-round hub of culture, featuring new plays and musicals, live music, international performance art, cabaret, community dialogue, civic engagement, and of course, Shakespeare.

FM: Through it all, the impulse has remained the same: to be a theater that is of, by, and for all people. Welcome to Public Square, a podcast of The Public Theater.

FM: Hey, Reynaldi.

RLL: Hey, Fernando.

FM: So we don’t even have to introduce ourselves, because we just did that.

RLL [overlapping]: Oh yeah, we actually know each other.

FM: We know each other! Um, it’s been a very, very busy summer at The Public.

RLL: Yes. Um, we had—it seems like forever ago—we had Much Ado about Nothing, directed by Kenny Leon, which is actually—if you missed that, it will be on PBS in the fall.

FM: Oooh, good plug.

RLL: Followed by Coriolanus, um, favorite Dan Sullivan returned. I saw Sullivan’s Cymbeline, which was astounding, and his Troilus and Cressida, and honestly, if ever there was a man who can take a Shakespeare that you may not have seen before and make it amazing, it is Dan Sullivan.

FM: More like Corio-rain-us, because it rained a lot. Actually some of the best performances you can see in the park are when it is, like, a light drizzle. Really adds to the drama.

RLL: That is true, and there’s also the famous story that I always hear from people—I feel like everyone I meet within that performance of Comedy of Errors with Jesse Tyler Ferguson—where the soundboard shorted out and it poured rain and it was an astounding evening of theatre. And the performance report said a hundred people stayed, but I swear I’ve met like, a thousand people who were all in that audience. They all have the same story.

FM: And, um, you know, speaking of great bolts of lighting, we’re gonna talk about Hercules.

RLL: We can’t not talk about Hercules.

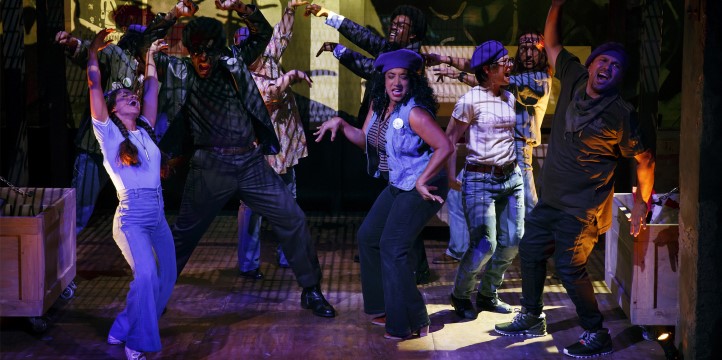

FM: [laughs] And just everything that goes behind the program Public Works, and for those of you that don’t know, this is Public Works’s Hercules.

RLL: It is two hundred everyday New Yorkers telling this amazing story that we all kind of grew up with, either as a story/myth or as a Disney movie, and sharing it with an audience every night, and it is just one of the most electric experiences of theatre I have ever had.

FM: And it’s a story about—which I love—it’s a story about humanity, and who better to tell the story about humanity than the, y’know, humans of New York City, the people that, you know, inhabit this beautiful city and this, you know, this planet.

RLL: And now it’s September. It is a new season here at The Public Theater. We have new banners outside with our new season look.

FM: Very pretty.

RLL [overlapping]: In case you didn’t know, we change our branding every year; hopefully we’ll have more to talk about that in a later episode. Fingers crossed.

FM [at the same time]: Fingers crossed? Uh-huh, jinx.

RLL: And we begin our season with the new musical Soft Power.

FM: Ugh, which is this beautiful kind of play—no, musical within a play within a musical within a play. There’s a lot of levels we’re going to discuss in a second. And we’ve got, you know, a dream team: David Henry Hwang, Jeanine Tesori, direction with Leigh Silverman, we’ve got Sam Pinkleton doing the choreography, um, and an incredible ensemble working on the show. It is going to be an absolute spectacle, delight.

RLL: And all backed by I think like, twenty-piece orchestra.

FM: Yeah, it’s gonna be a very big orchestra, a V. Big Orchestra. Um, so brace for impact, ‘cause it’s coming your way: Soft Power.

RLL: As an Asian American working in the theatre, and also someone who’s spent, and still spends, an unhealthy amount of time lip-synching to the cast album of Caroline, or Change, it is my joy to introduce our guests for this episode, David Henry Hwang and Jeanine Tesori, who will be chatting with us about the new musical Soft Power, which will be having its New York premiere this fall here at The Public. Thank you both so much for joining us this morning.

DHH: Thank you.

JT: Pleasure.

FM: This is the first time that we’ve had Tony Award winners on our podcast. Does that make this a Tony Award-winning podcast?

JT: Yes, and that’s why we have pastries.

FM [laughing]: That is why there are pastries! So, just kind of to start things off with probably the most difficult question, what is Soft Power?

DHH: Uhhh—

[laughter]

DHH: So, Soft Power starts out as a comedy that takes place in the U.S. in 2016, and then it morphs into sort of a fever dream of a, uh, imagined Chinese musical, which is about the events of 2016 in America, in which a Chinese producer falls into a romance with Hillary Clinton. And it’s sort of, like, a reverse King and I, the musical part, and it examines what happened and what is our soft power? That is, our cultural influence over the world and political influence over the world now, compared to China’s desire to gain soft power.

FM: Um—but you both have a lot of experience working with shows that are, kind of, you know, fall into that unconventional kind of form-busting style. Does that—do you set out to do that? Or is that kind of something that naturally happens? What’s your process there?

JT: Well, when David asked me about this, we were—we were talking about something else, and he said, “You know, I have this idea,” and I thought, Oh no, I hope it’s not a good idea, and then it was a really golden idea. And—and that was years ago. And then many things happened to David personally, to me personally, to the country, and so I feel like our form was busted as a nation. And, and so we—I think, I don’t set out to bust a form, because I’m still trying to figure out what the form of a musical is—they’re very slippery—but when something itself like, has an inverse or collides or has a form collision, then I get very interested in it, ‘cause it meant that we could follow some kind of unconventional roots.

DHH: I mean, I think I am really interested in form and what theatre can do, that we do better than other mediums, than film or television, both of which, you know, are mediums that Jeanine and I both work in also. But why do theatre, um, if you can’t sort of leverage the live experience in a way that’s going to be more viscerally exciting than you would if you work in these other mediums? So, in this case I think the idea of a play that becomes a musical, or a musical within a play, however we’re putting it these days, really is part of the way to tell the story theatrically. How does a relatively innocuous relationship in a play then eventually become mythologized and aggrandized in a musical? And what are—what are musicals really saying? I think in order to explore that question and tell that story, it made sense to do something that was a hybrid between a play and a musical.

FM: That’s the delivery system, right? Is that the right line?

DHH: Which is Jeanine Tesori’s term, now appropriated for this musical.

FM: Yaaay! Thanks, Jeanine.

[laughter]

JT: Well, you know, when we were talking about the idea of how you deliver—of how you deliver a story, of course the orchestral sound is—is so at the core of the American musical, the golden age American musical, and a seven-piece band or a twelve-piece band just isn’t, not in the traditional sense, because that’s based on rhythm, you know, pulse and rhythm, and you can’t really get long lines unless it’s a, you know, a classical group. And so we have a—we have 24-piece orchestra here, because there is a way that a song sounds when you have that behind it, and it’s—there is a physical reason for it in the science of what music can do, but the emotion of when strings play, that’s—that’s it.

RLL: Yeah, we really can’t talk about the show without talking about something like The King and I, and you know, we talked about it being a kind of reverse King and I, and for like, many Asians in musical theatre, the offerings have traditionally been King and I, Flower Drum Song, Miss Saigon, and all of them really do position Asian characters as outside or responding to Western influence. What has it been like to work with this amazing Asian ensemble to tell a story that comple—and develop a story, a new story, an original story, that completely flips that dynamic on the head, and really like, take charge of that?

DH: I—I think that one of the things I’ve realized as I’ve been working on this show is that, you know, sometimes people ask, “Oh, well when you were a kid, did you experience racism?” and I feel like yeah, there were probably some microaggressions and stuff; I don’t remember sort of big instances of racism, but what I do remember, uh, from being a kid was feeling oppressed by American popular culture, that every time an Asian character came on, I would sort of be cring—I would, y’know, because we would probably be the butt of the joke, or we’d be the enemy, or something like that. Um, so, actually when I was a kid I would kind of, if I knew there was gonna be an Asian character in something, I would go out of my way not to watch it, ‘cause I just thought it would make me feel bad. And so therefore, my entire adult life, in that, through that lens, has been about trying to grab the levers of American culture and redefine things from my point of view. And so this opportunity to create a sort of huge, lush musical in the tradition of Rodgers and Hammerstein, but from presumably a Chinese point of view, but really more my point of view, um, I think that’s what I’ve been working towards, I think, my whole career.

JT: I will say, it’s been really moving, you know, ‘cause I’m a white Italian American, and uh, I have really learned how I’ve also participated and now—and hopefully now contributed to including and expanding the repertoire for Asian Americans to play themselves. And, um, you know, there is—there is a great and necessary movement of color-conscious casting, and—and you know that’s different than color-blind casting, as we all know. But I think this is, as you said, the only—I think this is only the fourth musical in which the Asian American actor can play themselves.

But—but, um, this has been developed to examine the Asian American experience in America, and that—the conversations—’cause Leigh runs a great room, she runs a room based in love and rigor, and we are always checking in with each other ‘cause you have to, ‘cause it’s very—these conversations are painful, and not for me: I’m a visitor, and I’m also contributor, so it’s a very fine line. And listening to people, one woman, you know, I don’t know if it was in the cast or—she was saying, you know, when she felt like she has been often asked to bow or be sexually available in musicals a lot when she plays an Asian woman, and I—that really struck me, ‘cause I’d not really taken the time to sit with that. And—and so I feel like that experience for me has been incredibly important, and set a bar of how to work.

DHH: I also want to just point out that historically, um, there have, before this show, there have only been two or maybe three—depending on how you count it—musicals that center around Asian American stories. There’s a fair number that are set in Asia, but if you look at Asian American stories, in the history of the American theatre, you have Flower Drum Song, Allegiance a few seasons ago, and then if you wanna count my revisical of Flower Drum Song, that would be three. So it’s two and a half.

FM: Our special guest Jeanine Tesori is no stranger to The Public. In 2013, a little show called Fun Home premiered on our stage, with music by Jeanine Tesori and with book and lyrics by Lisa Kron. Lisa joined us recently as a keynote speaker for one of Public Forum’s Civic Salons. Here’s an excerpt.

LK: I want to say that although art and activism are not the same, I do believe that all art is political. For the purposes of this argument, I’m going to define “political” as “having to do with the way resources are allocated across society”: healthcare, education, and money, time, representation, narrative representation, and so on. In this country, identity—race, gender—is a political factor because we have made those things determinate of resource allocation.

So, using this definition, all plays are political, and there are two types of plays: plays that have an overt concern with resource allocation, and those that are satisfied with the current resource allocation. One of the things plays can do for us is they teach us how to have empathy for fellow human beings, and we often say that we shouldn’t judge our characters, and I think that’s right, in a way. But I think that having empathy for humans doesn’t mean actually having no moral judgement; it means, I think, making clear that people have volition, they make choices, they take actions, and those actions affect other people.

We all have an effect on each other—we’re all interconnected. And maybe this is where the morality of a play is located: a character does something, their action has repercussions; who is affected by that action and in what ways? Who and what is the playwright tracking? I think maybe the morality of a play is located in the playwright’s map of consequences, of the consequences of the actions taken by her characters.

FM: Spoiler alert! If you all don’t know, Hillary Clinton is in the show—well, she’s not in the show, or she is—there is someone portraying Hillary Clinton.

DHH [overlapping]: A character called Hillary Clinton.

FM: A—a character called Hillary Clinton, which is kind of the question that leads to the question where, knowing that you’ve put a person that is a political figure in your show, how do you come up with a vocabulary, a rhythm for this person that actually exists?

DHH: I mean, again, if we look at King and I as a jumping-off point, um, the actual king, historically, is incredibly different from the king that’s in the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical. So there’s sort of a long tradition of taking real-life characters and—I would say particularly in musicals but also certainly in movies and plays—and um, creating a mythology around them. And I think that’s what we’re really doing here, uh, the conceit being that it’s a Chinese musical, which, uh, mythologizes the events of 2016, and therefore creates a kind of fictional Hillary Clinton avatar character.

JT: You know, it’s—the, um—we really shouldn’t be getting our history from musicals.

[laughter]

DHH: From this one. Can you—[inaudible]

JT: I mean, some. I mean, you know, Hamilton and, um, certainly Lin has been incredibly sage about—um, he’s a scholar, and David’s a scholar, but that’s not where we should be getting history. So when you ask, I think, the average person, “What was the king of Siam like?” I bet that they are going to think that that’s what the king was like, because that’s a kind of soft power that was delivered as a cultural message. And it goes right into the center because it’s—he’s funny and he’s endearing and he just whips slaves and that’s bad, and—and it’s an incredibly beautifully-constructed musical. And I think it really looked at that, and they looked at that, they were responsible, wonderful writers, writing in a time, as were we twenty years ago, and the conversation has changed.

And—and the—I think the moral imperative is to really keep up with the conversation and further it, and I do think David’s idea and personal risk of putting his own story inside it—and I think reluctantly—but, having worked with David now, I see that he knows he should, he knows he wants to, and there is also a reluctance to put it on, and that to me has been wonderful to feel—to feel that tug. But I think that when you think of Hillary Clinton, what we decided is that she had a lot of agency, and there was a lot of rhythm to it, because she had a lot to get done! And there was that time when we really thought, Oh my god! This country’s just gonna take off with a Madame President! And that has a rhythm to it, and it turned out not to be the case.

FM: The show—no pun intended, and don’t kill me for this—hilarious. Hillary-us.

JT [softly] Wow.

[laughter]

FM: Didn’t—I wish you could see Jeanine’s face.

JT: Went from the best Friday ever, and it took a real downturn.

FM: It just plummeted, it just plummeted.

JT: I’m gonna take those pastries—[grunts]

FM: Jeanine’s walking out of the room. You can’t see it right now, but that’s what’s happening. [more laughter] Um, but the show has a lot of humor in it, and it features this, you know, this enormous, lush orchestra—we’ve kind of touched on this before—and it’s so, you know, it’s your story, I mean, there’s a lot of vulnerability in there, in the show, David, because it’s your story, you know, your real story. Um, why make this a musical comedy? Why make it funny when, you know, it seems like the last thing a lot of us wanna do is laugh right now?

DHH: Um, I think, number one, all of my work has humor in it, so I’ve generally felt that humor, particularly when you’re dealing with some difficult or uncomfortable subjects, humor literally allows us to take in ideas. I feel that the notion that you laugh and you breathe out and then you breathe in, I feel that it’s literally an openness that makes us more receptive to things that are uncomfortable. And then, second of all, that we’re again dealing with a kind of musical comedy tradition, so it’s necessary if we’re going—I mean, there was a period I think, early on in the development of this when—tone has always been a big issue and a big question, like, what kind of musical is this? Is it—is it a Disney musical? Is it Les Mis? And, you know, we’ve sort of settled around a form that feels like our initial model, which is an R&H. But those are, you know, the R&H musicals are serious; they’re dramedies. They’re all, um, very—they’re about something, and most of the time the humor—very rarely do they reach for a joke; you know, the humor always comes out of the situation and I hope that that’s what we are doing as well.

RLL: The show’s first reading occurred—is it literally the day after thr 2016 election? Day of?

DHH: Well, the day of, so we had all voted, and then we—

JT: We all had those stickers on.

DHH: Yeah.

FM: Oh.

JT: And then we peeled them off and there was blood underneath.

[laughter]

RLL: So, you know, knowing that that was like—that was kind of the beginning of the show, and now, as it’s developed and had productions, we are heading into the next election cycle: what has it just been like to be so immersed in this unpacking of democracy and culture as these things are happening in the real world? And like, how—have you tried to keep what’s happened in the world from affecting the process too much? Do you respond to it? How has it just kind of like affected your perception of the work, or even like democracy in America?

JT: That is a great question, and I think, you know, musicals are often not light on their feet; one of the few times that I’ve been at the center of a—you know, Fun Home and the day that the Supreme Court decision went through, and we were doing a matinee, and that was one of the few times where the—again, the national conversation met a musical. Musicals are not often, because they take so long to write, they’re often five or seven years behind the times in which they were started, and so you have to be very prescient, and David was, Tony Kushner is; there are very few writers I think who really think, “Okay, this is happening, and five years from now”—that’s the development usually, five to eight years of a musical—“this is going to be right at the center of this.” And this particular—I think because David had this idea, and it was going in a certain way because Hillary was going to win, and then it went a certain other way at a crucial juncture for the musical itself when she didn’t win and turned out to be, as David said, unfortunately very good for the piece dramatically. And now I th—how many times a day do we constantly email each other? “This is happening.” “Did you see this about China?” “Did you see this op-ed? This exa—” And we’re constantly, you know—the amnesty warning about don’t travel—

DHH: Travel warning. Yeah.

JT: The travel warning for— There was a, David wrote this whole thing about “don’t travel to America,” and people would laugh, and then it happened and we were like, “Jesus, what is going on?” And—and it’s really exciting, unfortunately, for this musical to be reaching the headlines of the papers.

DHH: I mean I think when the election happened, um, a show that was potentially about China gaining soft power—could China gain soft power?—became about, could America retain our soft power? which actually is, of course, much closer to our hearts as Americans. So, you know, there’s some things that were reasonably easy to predict after the election, I was—probably we were gonna get into some conflict with China, um, just given the mentality of the folks that would be part of the new administration, um, and then there are things that are just, you know—that were just kind of, “Wow! That happened!” whether it’s the amnesty travel ban, or the picture of the president with all of the fast food, um, when he invited the football team over.

FM: Great point.

DHH: So, things that felt like there—you know, they may have been prescient, um, but were really just kind of logical extensions of what seemed likely to happen once the election result was announced.

FM: So one more kind of major question. So people, um—you know, someone walks into the show; at the end of the show they get up, standing ovation, and they walk out. What do you want that audience member to take home with them? Or what do you hope they take home with them, they get on that subway car, in that car home?”

DHH: I think there were a lot of tears in the theater, a combination of kind of release and oddly, hope. You know, there’s a way in which this show worked to both encapsulate some of—all the things, the complicated feelings and the intense emotions we’ve been having since the election—and also, you know, maybe point a way towards a—some way to continue to believe that the country can, uh, hold together, and the things that we believed in as Americans when we were growing up still have value. And Jeanine, you talked—you know, you always sort of talk about a kind of optimism that musicals need to have, so I’ll pass it to you.

JT: Well, I—I do feel like, you know, maybe because I was fed a steady diet, like all of us, of our democratic system, and—I do feel like when I write a musical, there is a moral imperative of hope at the end. I—I just can’t end it on a minor chord; I mean, that’s why I write opera. But um, I think the idea, and I’m still, as we’re writing this piece, I’m so incredulous that we have someone whose relationship to the truth in off—you know, at the head of this country—is so shaky and so slippery, and we were raised to believe that the president of the country was, had to be, you know, a historical figure and a scholar, and that incredible disappointment that I think goes, rattles, down through the system, looking at the system that allowed it to happen, wanted it to happen, and yet—by popular vote—didn’t let it happen, is such a complicated process of reassessing this system that we never questioned, so that’s one, and then to do it while there’s a beat going oom pah oom pah oom pha da da duh, and it’s like, very confusing, and to still stand by it and—and also to wonder what it’s like, sitting with an Asian American community, and hearing the words “perpetual foreigner”, I just didn’t, growing up, I didn’t grow up considering that, and I’ve done a lot of work inside the African American community with—you know, in terms of the—Caroline, or Change, the opera Blue, um, running programs at Broader Way—I have never, I have been very naive about the Asian American community theatrically, and—and the way that, you know, David describes “Not where is your family from” and I think, Oh my god.

You live inside—it’s such a bubble, and I felt pretty evolved until I worked on this show. And as Oskar Eustis who—we’re sitting in his house right now—he always points out that democracy and theatre, they have a deep relationship, that you were not allowed to lead unless you saw a play in Ancient Greece, and I think that that idea that you radically can empathize with someone else and walk in their shoes, so to enter The King and I and wonder what it’s like to not be the person who is being visited, but the visitor, and what if that person—what if everything was reversed, every single thing? And I—so I think that’s also what—that I hope people walk out of the theatre with, is wondering if they were driving the cab instead of riding it, or if they were behind that counter instead of sitting at it, even non-transactional things, what it would be like to switch places.

RLL: Jeanine, David, thank you so much for joining us this morning.

FM: Thank you, thank you.

RLL: I know you have a lot of long days ahead and we are so excited for Soft Power.

LW: My name is Liza Witmer, and I am one of the company managers here at The Public Theater. And uh, I’ve been here for about seven and a half years at this point.

FM: I love that.

LW: Mhmm.

FM: And so, for the folks at home, can you tell us: what is a company manager?

LW: Well, folks at home, um, a company manager is part of the administrative staff that is charged with taking care of our artists. So it takes a large emotional toll frequently to do a play well over and over again, eight shows a week, and so my job is to help make sure that all of the non-show-specific needs that an artist might have are taken care of; so, we’ll do meet ‘n’ greets and catering and payroll and house seat requests, and medical stuff, if somebody’s injured on the job. Um, recently we’ve started doing a little bit of mental health work for connecting artists that are struggling with some tough content of the work that they have to do over and over again—it’s a very vulnerable job, and so our jobs are to help take care of them—

FM: I love that.

LW: —in all the ways in which they might need taken care of.

FM: In your day-to-day, what excites you about your job? What—what do you wake up feeling really excited to tackle?

LW: [laughs] So, there’s no like, typical day-to-day, which is kind of cool actually about it.

FM: Feels that way.

LW: Yeah. Um, uh, the thing that I really love about my job, especially working at an institution, as opposed to commercial company management on, you know, Broadway, is that I love that I am—I have one leg in the administrative offices and I have one leg in the—the company—each individual company. So I am very much a part of the staff here, I have a permanent desk, I have the stability of a job, a full-time job here, and at the same time, I get new casts every three or four months, and so I get a whole rotating group of like, wonderful people who are just, you know, everyone’s just like happy to be there and it’s—uh, that’s a thing that I really love. And I love getting to know in each company—of course you know there’s many, many, many people that we interact with and we can’t have close relationships with all of them—but in every company, there’s at least a few people that, you know, we have a really wonderful human connection with. And so, getting to know what people need and what would make their lives easier, that’s an amazing part of the job.

FM: Oh, yeah.

LW: And being able, you know, to have them say, “You know, I feel very taken care of and I feel very safe here” is—if we’re doing our job well and you know, there are many contributing factors into that, but I—being able to hear that is really gratifying.

FM: The—the feedback.

LW: Yeah.

FM: And let me just say that you do.

LW [overlapping]: Oh! Thank you.

FM: You do do an excellent job. Liza’s actually the company manager on Soft Power, which we’ll be discussing a lot this episode.

LW: Yay!

FM: So—yay! And I guess the last thing to kind of end with, uh—what advice would you give to someone who maybe wants to get into this line of work? Or maybe they don’t want to get into it, but, y’know, here’s your sales pitch.

LW: Yeah! Um, well, the cool thing about I think the theatrical industry in general and arts administration is that the landscape is changing a little bit. It used to be that you, you know, you went to a liberal arts education and you got an internship, or several internships, if you could afford to do that, and then you did—you know, you grabbed onto a mentor and you kind of like led on through that, and I think that it’s really really important to say and to hear that there are lots of avenues and pathways into a career like this. So, if you have caretaking responsibilities in any kinds of jobs, and you’re interested and like, the idea of caretaking of artists sounds useful to you, use that—use those, those adjacent skills. It may not say, like, “I don’t have any theatre training!” but in reality, you have a lot of the same kind of skills that you need. And arts administrators, I encourage you to look for those comparable skills as well.

FM: Yaaay! Agreed. And it’s a really cool industry to be a part of, so I’m glad that I’m a part of it; I’m glad you’re a part of it.

LW: I’m glad to be here.

FM: And I am so glad that we got to talk. Thank you, Liza.

LW: Thank you.

RLL: We had a great time kind of hearing David and Jeanine talk about what Soft Power is as a musical. And it’s really kind of gotten us thinking just, like, soft power as a concept, achieving change through cultural influence, and other musicals that actually use this concept.

FM: The Sound of Music.

RLL: Yeah.

FM: Which kind of in a way follows a similar kind of structure as The King and I, when you think about it. It’s this—this nanny comes into this, to this home, to this place, and breaks down the walls and teaches the Von Trapp children music. Am I going—am I, like, going too far on this?

[laughter]

RLL: When you think about it, it’s the same principle, because she’s bringing, like, the culture of music into this land where there is not music and she gains success by manipulating that culture for her own benefit. I’ve—I’m really hoping that we can inspire people everywhere listening to this, you know, kind of how when the Met Museum had their gala about “Notes on ‘Camp’” and for a long time, everyone was suddenly an expert on camp and everyone had all these thoughts, like, Is this camp? Is that camp? I want soft power to be the new camp.

FM: Yes. And not that it has anything to do with soft power, but Six: it’s just the best.

RLL: It is the best, it really is. Wait, no, let’s think about this, though.

FM: All right, let’s think about it.

RLL: I’m trying to—I’m now thinking, do any of the queens in Six exert soft power?

FM: Wait. Hold on. We can figure this out.

RLL: Okay.

FM: First of all, I’m definitely, probably—I think I’m a Catherine Howard. You know what you are?

RLL: I—I’m Heart Of Stone…

Public Square is a production of The Public Theater in New York City. Your hosts were Reynaldi Lindner Lolong and Fernando Masterson. Special thanks for this episode to Jeanine Tesori, David Henry Hwang, Liza Witmer, and Lisa Kron. Music for this episode was by Michael Friedman, and audio engineering and editing by Drew Broussard and Dani Lencioni. You can find out more about what’s going on at The Public Theater by going to www.publictheater.org.